Swing bowling is one of cricket’s most fascinating and deceptive arts. It’s the craft of making the ball move unpredictably through the air, baffling even the most seasoned batsmen. Mastering swing requires not just physical skill but also an understanding of aerodynamics, seam position, and conditions. This blend of science and subtlety is what makes swing bowling such a defining aspect of the game.

1. The Physics Behind Swing Bowling

At its core, swing bowling relies on the aerodynamics of a cricket ball. The ball has two sides — one shiny and one rough. When a bowler delivers the ball with the seam angled slightly and the shiny side facing one way, the airflow over the ball becomes uneven.

-

Laminar flow occurs on the smooth, shiny side (where air passes smoothly).

-

Turbulent flow happens on the rough side (where air gets disturbed).

This difference in air pressure causes the ball to swing towards the rough side. Factors like seam position, wrist angle, release speed, and humidity affect the degree of swing. Cooler, overcast conditions often enhance swing because of increased air density and moisture.

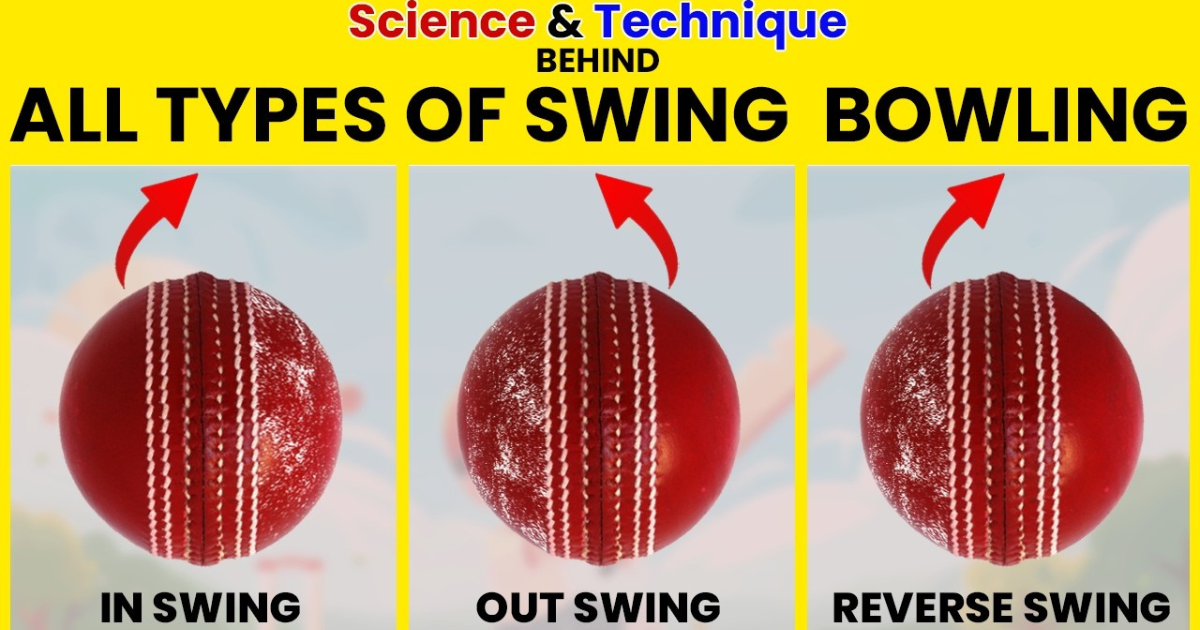

There are three main types of swing:

-

Conventional Swing: Usually achieved with a new or moderately used ball. Moves towards or away from the batsman depending on the seam position.

-

Reverse Swing: Happens when the ball is old and one side is much rougher. The ball moves in the opposite direction of conventional swing — a phenomenon that occurs at higher speeds.

-

Late Swing: When the ball deviates just before reaching the batsman, making it extremely hard to read or play.

2. Techniques for Effective Swing Bowling

Achieving consistent swing requires fine-tuned mechanics and constant practice. Here are some key techniques that define the art:

a. Grip and Seam Position

The bowler holds the ball with the seam upright, usually between the index and middle fingers. The shiny side faces either leg or off side depending on whether the bowler wants to produce inswing or outswing.

b. Wrist and Arm Control

For outswing, the wrist should be slightly behind the ball, with the seam angled towards first slip. For inswing, the wrist faces inward towards fine leg. Maintaining a steady wrist position at release is crucial for accuracy.

c. Speed and Length

Conventional swing works best at medium to fast speeds (125–140 km/h). The ideal length is full or good length, giving the ball time to move in the air. Reverse swing, on the other hand, requires higher speeds — above 140 km/h — to generate late movement.

d. Use of Conditions

Overcast skies, green pitches, and new balls all favor swing. Smart bowlers learn to read conditions and adapt their style — for example, keeping one side shiny in dry weather or using sweat strategically to maintain balance.

3. The Masters of Swing Bowling

Over the years, several bowlers have turned swing bowling into an art form, dominating matches across generations.

-

Wasim Akram (Pakistan): Known as the “Sultan of Swing,” Akram mastered both conventional and reverse swing. His ability to move the ball both ways at express pace made him nearly unplayable.

-

James Anderson (England): The leading wicket-taker among fast bowlers in Tests, Anderson’s control over seam and late swing has made him lethal in English conditions.

-

Waqar Younis (Pakistan): A pioneer of reverse swing, Waqar’s late inswinging yorkers terrorized batsmen in the 1990s.

-

Dale Steyn (South Africa): Combined raw pace with precise outswingers, often setting batsmen up beautifully with his movement.

-

Trent Boult (New Zealand): Modern-day swing specialist, famous for his smooth action and ability to move the ball in both directions early in the innings.

-

Bhuvneshwar Kumar (India): A seam bowler who relies on precision and late movement rather than pace, particularly effective in limited-overs formats.

Each of these players embodies the adaptability and intelligence required to exploit every condition — be it the damp mornings of England or the dry air of the subcontinent.

4. The Modern Evolution of Swing

In the age of T20 cricket and heavy bats, swing bowling faces new challenges. White balls tend to lose their shine quickly, reducing the window for movement. However, bowlers have evolved — using seam variations, slower balls, and cross-seam deliveries to retain unpredictability.

Technological advancements, such as ball tracking and aerodynamic research, have also deepened our understanding of swing mechanics. Still, it remains as much an art as a science — dependent on touch, instinct, and timing.

Conclusion

Swing bowling represents cricket’s most subtle and intellectual weapon. It’s a test of both skill and strategy, where the bowler’s craft can turn an ordinary delivery into a match-winning moment. From Wasim Akram’s magical spells to James Anderson’s masterclasses at Lord’s, swing bowling continues to remind us that in cricket, brains and precision often triumph over brute force.